Later,

I began reading historical novels, progressing from Geoffrey Trease to Rosemary

Sutcliff and later to Mary Renault, among others. I was always very firm, though, that I wanted

stories about history, not just

costume stories set in the past. That is, stories that showed me a different

era, its different culture and values.

It's

sometimes said that historical fiction began in the 19th century with Sir

Walter Scott, which seems unlikely on the face of it. There have always been

stories set in the past, right back to the oldest surviving fictional work, The Epic of Gilgamesh. Written in its

earliest surviving form around 1800 BC, it was set about seven hundred years

earlier.

The

same can be said about Homer's works, believed to have been

"written"* around four hundred years after the events they describe

took place. Or didn't take place, but the thing that prevents the Iliad and the Odyssey from being historical fiction isn't that the Trojan War

might never have happened. It's the fact that Homer makes no attempt to portray

late Bronze Age Greece, instead presenting a society very much like the one he

lived in.

The

same was true of the mediaeval romancers, from Chrétien de Troyes to Thomas

Malory, whose stories were theoretically set in 5th century Britain or the 8th

century Frankish Empire, but were actually an idealised picture of the writers'

own times. Very idealised, in fact. For the most part, the romancers seemed to

be giving a vision of how their society should have been, rather than how it

was.

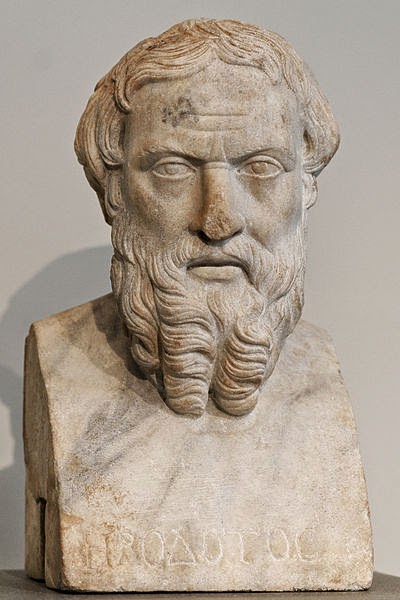

That

isn't history. The Greek word historia originally

meant inquiry or investigation. Early authors wrote "investigations" into

various topics, but the word took on its current meaning when Herodotus

undertook to investigate the root causes of the war between Greece and Persia.

His criteria for what constituted historical events may have left something to

be desired (he identified one of the earliest phases of the quarrel as Zeus's

abduction of Europa) but his approach was essentially sound: to understand the

present by first understanding the past.

Later

Greek and Roman historians, such as Thucydides and Tacitus, developed the

discipline further, but mediaeval "history" devolved into little more

than a recital of events, real or imagined. It was in this climate that the

word history was co-opted to refer to any tale: it's still histoire in French, and was reduced to story in English. History as we know it wasn't really reborn until

the Renaissance** and took a quantum leap in the 18th century with Edward

Gibbon and The Decline and Fall of the

Roman Empire.

Nevertheless,

there was historical fiction long before Scott, particularly in two widely

separated cultures. The Chinese novel reached the beginning of its classic

period in the 14th century, and two of the earliest great works were

unmistakably historical in theme. The

Water Margin told the story of a group of outlaws a couple of centuries

earlier, while The Romance of the Three

Kingdoms went back a thousand years further. While these novels' motives

seem to have been partly to illuminate their own turbulent times by presenting

parallels from the past, they portrayed history in ways that the epic poets and

romancers of Europe hadn't attempted.

The

other haven of early historical fiction was Iceland between the 12th and 15th

centuries, where some of the earliest European novels were written in a culture

whose literacy rate wouldn't look too shabby today. Some of the sagas retold

the old legends of gods and heroes, but most were set in 10th century Iceland

and explored the processes, a little reminiscent of the taming of the Wild

West, by which the anarchic settlers gradually coalesced into the Icelandic

Commonwealth with the world's oldest parliament. One or two, such as Ari's Saga, dealt with more recent

events.

Genuine

historical fiction occurs elsewhere now and then. Quite a few of Shakespeare's

plays are certainly historical and arguably (Richard III, for instance) fictional. On the other hand, while many

of the Gothic novels of the 18th century are set in the past, this is largely

no more than a conveniently dramatic setting.

Scott

wasn't quite the first modern historical novelist, but he was the one who made

it fashionable. He was followed by, among many others, Marryat, Blackmore and

Stevenson in Britain, Fennimore Cooper in America, Hugo and Dumas père in

France, and authors in many more countries. By the 20th century, historical

fiction was well established.

As

in ancient times, setting a story in the past doesn't necessarily make it

historical fiction. The Hungarian critic and philosopher György Lukácz argued

that Scott was the first true historical novelist because he treated the

historical period as socially and culturally distinct from his own time. Though

I'd argue that this could also be said of the Chinese and Icelandic works

mentioned, it does rule out many works, notably a large proportion of costume

romances, which aren't particularly interested in exploring the period, as well

as many recent "historical" TV shows where the characters are little

more than modern people in fancy dress.

Historical

fiction is usually associated with periods substantially in the past, but

arguably it can be set within living memory. The best-known historical novel by

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities,

was set little more than sixty years before its publication, and Hugo's Les Misérables was a good deal more

recent. Historical fiction can certainly be written now about World War 2, and

perhaps a good deal later. Perhaps your attitude to that will depend on your

age, but it can be disturbing to have events you clearly remember described as

history.***

Whether

you set your historical novel in Pharaonic Egypt or in the 20th century,

though, it must be approached with the curiosity and analysis — the investigation

— of a historian. Otherwise, it's just a bunch of people in nice clothes acting

out a modern story. Which can be fun, but it isn't historical fiction.

*

It's unlikely Homer actually wrote his

work down. Writing disappeared in Greece after the fall of the Bronze Age

palaces, since its main function was for palace records and accounts, and was

probably not re-introduced till after Homer's time, via the Phoenicians. The

only oblique reference Homer makes to writing (in Glaucus's story of

Bellerophon) suggests he'd heard of it but had no idea what it was.

**

I'm referring here to the European study

of history, which is what most concerns us in the English-speaking world. The

discipline flourished in other parts of the world, such as China and the

Islamic Empire.

***

Such as the recent "historical"

Doctor Who stories set in the

seventies and eighties. Puh-lease.